A new data retention law to Germany – this time in accordance with the Constitution?

Author: Jacqueline Abreu*

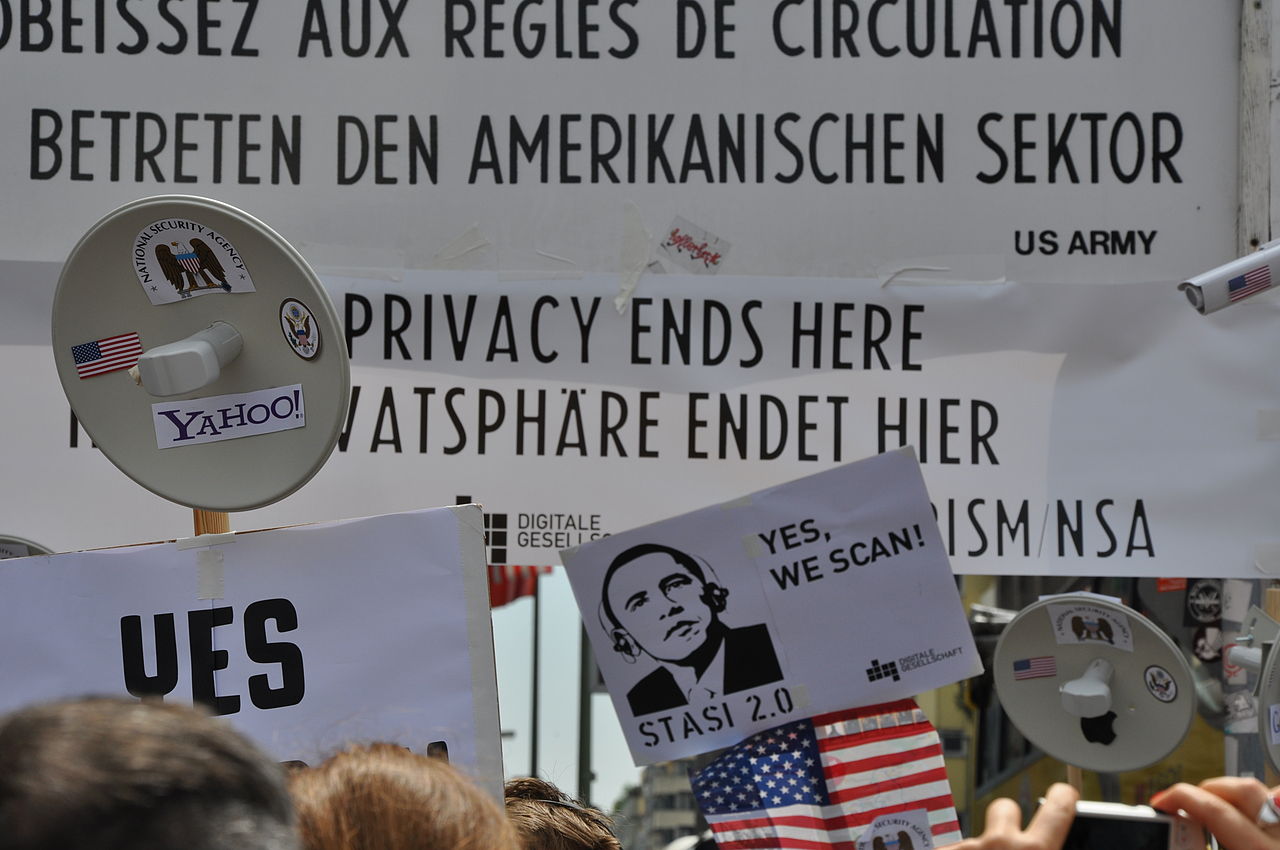

Justice Minister Haiko Mass (SPD) and Interior Minister Thomas de Maizière (CDU) announced last Wednesday (04.15.15) the plan to reintroduce in Germany the obligation to retain metadata generated by the use of telecommunication services. The proposal can be seen as a legislative effort to adjust data retention rules to the principles set by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) and Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court (FCC), who declared, respectively, EU’s Data Retention Directive of 2006 and Germany’s Implementation Act (which brought the Directive to national law) invalid on grounds of fundamental rights violations. It is a new attempt to find a constitutional balance between freedom and security in regard to data retention, as the Courts rejected the first one.

When data retention was first introduced in Germany back in 2008, telecommunication service providers were obliged to store metadata generated by user communications for six months, in order to ensure their availability to security authorities for the purpose of investigating crimes and averting dangers. Fixed network, mobile and Internet telephone service providers were thereby obliged to retain metadata regarding calling and called numbers, date, time and duration of the call, besides location data in the case of mobile calls and IP addresses in the case of Internet telephony. For Internet access providers the retention concerned IP address, date, time and duration of the connection; email providers, in their turn, had to store email addresses involved in the communication, subject, data and time of transmission and receipt.

It didn’t take long until a case was brought against the law before Germany’s FCC, which ultimately declared it unconstitutional back in March of 2010. Very elucidative to the current political landscape and remarkable in the decision is the fact that the FCC did not hold data retention as such unconstitutional. It was rather its configuration in the Data Retention Implementation Act that did not come to terms with the rights to secrecy of communications and informational self-determination. In the face of its extent and scope, the possibility of creating personality and movement profiles by mining the data, the potential chilling effects generated by the sense of being watched and the risks of data leakage and abuse – all concerns related to protecting freedom, data retention could only be justified for security interests if requirements to its proportionality were at hand.

To this effect, the FCC held imperative to a data retention act “in accordance with the Constitution” the establishment of strict and precise rules regarding data retrieval, use and security as well as sanctions to the case of rule violations, user notification rights, data use transparency rules, among others. As by then the very Data Retention Directive had also been challenged at European level, it wasn’t the appropriate political momentum for German legislators try to enact a new law right after the decision of the FCC. When in April of 2014 the European Court of Justice declared the Directive to be invalid in very similar terms to FCC’s decision, also not prohibiting data retention in principle, German politicians who favor the measure began to work again for a compromise in Congress that could make the reinstatement possible.

In the guidelines announced by the German government this week, the effort to find a balance between security interests and the protection of fundamental rights at the light of the concerns expressed and the parameters fixed by the FCC (and the EUJ) is remarkable.The retention period would be reduced from six months to ten weeks (down to only four in the case of mobile telephony location data); in regard to data categories, the change would be the exclusion of mandatory retention of email communication metadata. The proposal also commits itself to restricting retrieval of data to cases of serious crimes explicitly stated and passing strict rules on data security and user notification. The retrieval of retained data would always depend on a judicial order and would be prohibited when related to people working under professional secrecy.

Notwithstanding the new and “better” terms, the new proposal still finds much resistance. In fact, the opposition to it calls attention to a core problem of mandatory data retention, that remains in the new proposal and threatens this new attempt to find the constitutional limits of restricting freedom for security reasons: the obligation to retain data is still fundamentally groundless, that is, disconnected of suspicious behavior or concrete danger, even if the retrieval is not. There are many Germans who, before contenting themselves with safe data storage and strict access (and trusting in the enforcement of the rules), do not accept being treated as potential criminals. This matter must be taken seriously in the public debate on the new proposal and shall likely bring the future law, if it passes, again before the FCC.

* Jacqueline Abreu completed her Bachelor Studies in Law at the University of São Paulo and is currently a LLM Candidate at the Ludwig-Maximilians University of Munich.