Indemnity for moral damage threatens freedom to do humor on the Internet

The idea that fundamental rights are not absolute and therefore admit restrictions seems to be sedimented among Brazilian judges. In almost every judicial decision analysed in a research conducted by InternetLab, an independent research center that focus on law and technology in Brazil, the argument was invoked as a premise to the rulings involving freedom of speech and humor on the internet. No problem up to there. In fact, as Robert Alexy states, to settle cases involving conflicting fundamental rights, judges should weigh and determine which of the conflicting interests has a greater weight on the concrete case [1]. In the case of the court decisions that InternetLab analysed, the problem is on the results of this weighing, which suggests a disfavor of the right to the free manifestation of thought in relation to others, like reputational rights such as honor and image.

The goal of InternetLab’s research was to use humor on the Internet as a way to evaluate how the Judiciary Power has been deciding cases involving freedom of speech. The research analysed decisions of the second instance (appealing courts) involving civil matters in all state justice courts of the country. To search for the decisions, two sets of search terms were combined: (i) the first related to humor, with the tags “humor”, “satire”, ‘parody“, “joke”, “sarcasm”, “comedy”, “comic”, “irony”; and (ii) the second connected to the availability of the content on the web, with the words “internet”, “online”, “virtual” and “network”. The combination of the sets resulted in thirty-two pairs of keywords, that led to a group of 1.004 decisions. Of those, 148 were selected as relevant, out of which 119 were appeals and 29 were motions/bills of review. The decisions were coded according to different criteria, mostly with the aim to trace a profile of their plaintiffs, defendants, requests, legal basis and results.

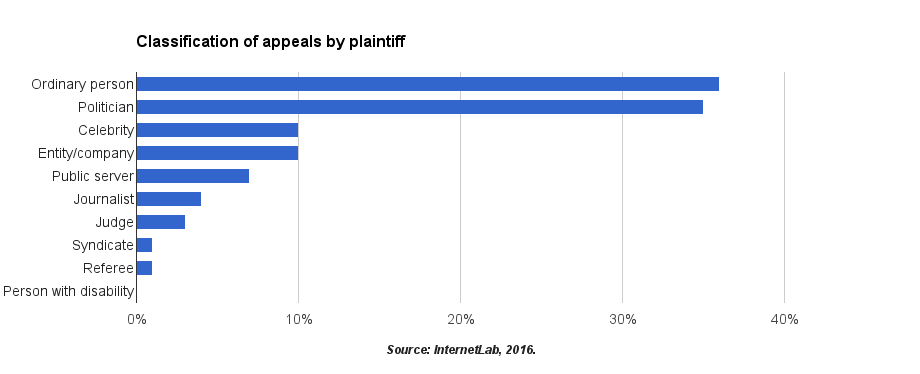

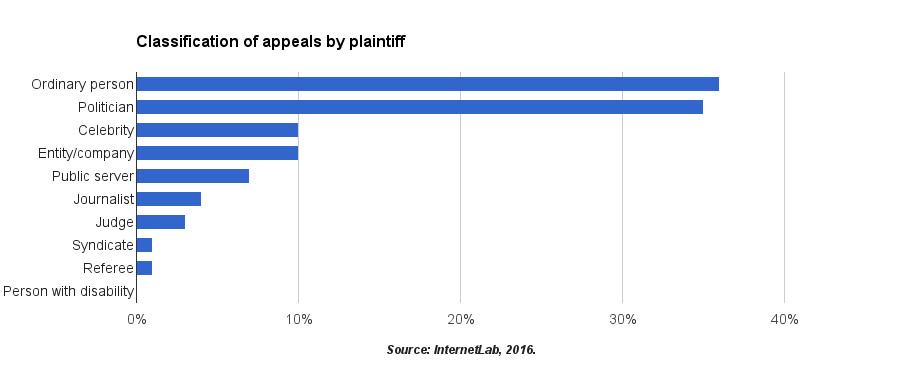

Some preliminary data of the research was disclosed on August 9th, in Brasília, on the Google-Abril Forum of Freedom of Speech that had the participation of the Honorable Justices Gilmar Mendes (Constitutional Supreme Court), Henrique Neves (Superior Electoral Court) and Ricardo Villas Bôas Cueva (Superior Court of Justice). In the case of the appeals, what draws the attention is the fact that ⅓ of the lawsuits was filed by politicians. This is particularly interesting given that cases of the Electoral Justice were not analysed:

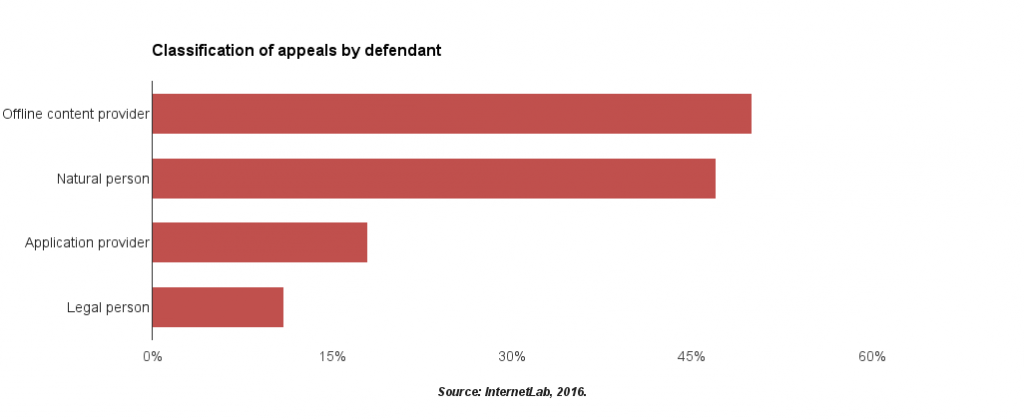

On the defendants’ side of the lawsuits, typically we could find providers of offline content, like newspapers and television stations, but that also keep online channels on which the humoristic content that drove the lawsuits was made available. In general, they are also accompanied by the authors of the contents, like cartoonists, humorists and ordinary people.

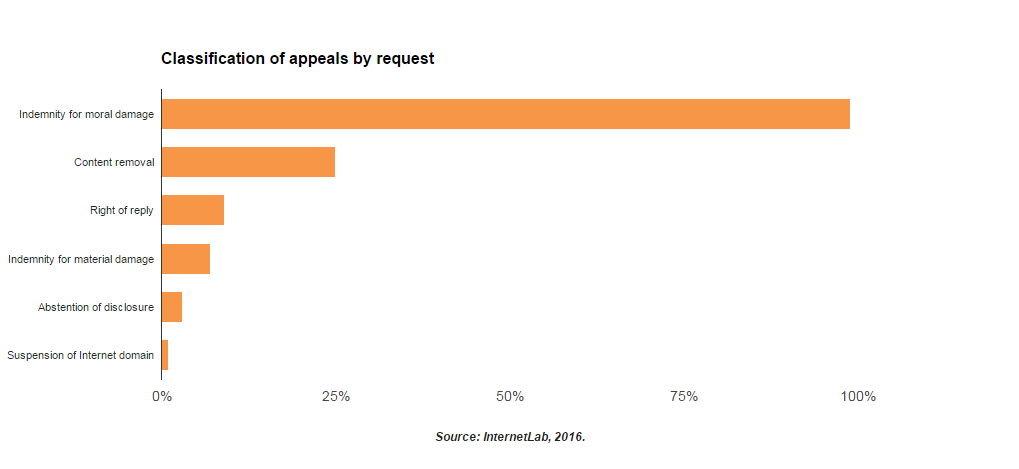

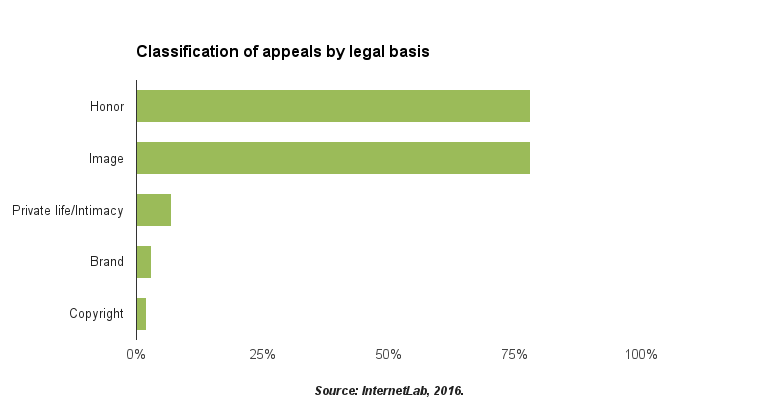

In relation to the requests, the indemnity for moral damage is sought in almost every lawsuit, which can also be related to the main legal grounds presented in the lawsuits: the right to honor (78%) and to image (78%). This is because the Brazilian Federal Constitution, in its article 5, X, establishes the right to indemnification in cases of violation of these rights [honor and image]. In the same way, it guarantees the free manifestation of thought (article 5, IV).

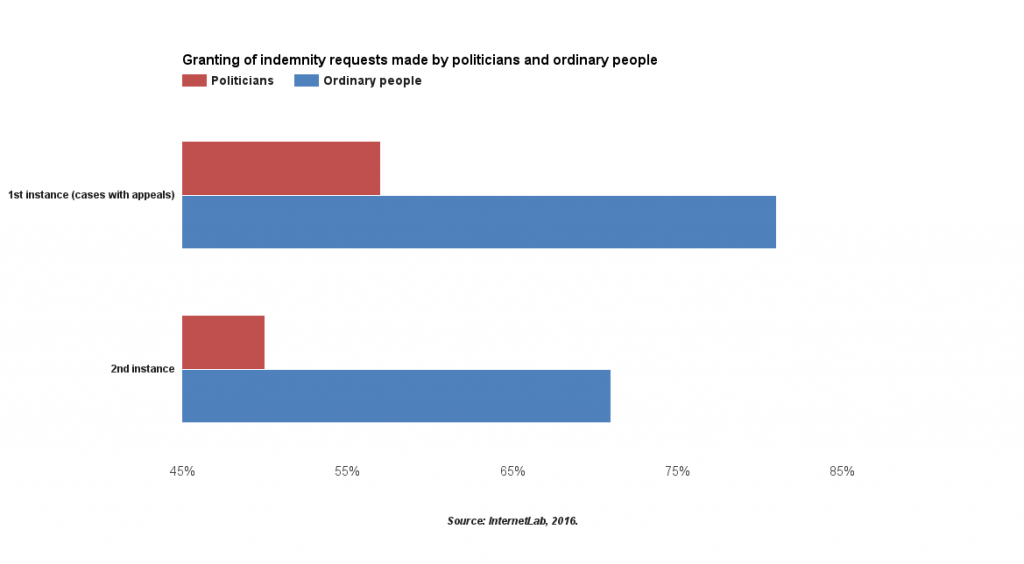

The results of the analysed appeals suggest that the Judiciary Power is still quite lenient in relation to the requests of indemnification by damage to the honor and image (“moral damages”), which means that, strictly speaking, on the weighing between freedom of speech and those rights, the last ones prevail. On the group of actions moved by ordinary people, in 71% of the appeals the indemnity for moral damages is granted; in 81% of those lawsuits, the indemnity was granted by the judge of the first instance. The numbers are not so different as they should be in relation to the lawsuits filed by politicians: in 50% of the appeals, the politicians were granted moral damages; in almost 60% of these lawsuits (only those that reached the higher courts, as these were the only ones we analysed), the claim for moral damages was granted by the judge of the first instance.

The fact that the average value of moral damages arbitrated for politicians (R$16.3000,00) was higher than the value arbitrated to ordinary people (R$13.800,00) is even more surprising.

Numbers like these demand reflections on the weight given to freedom of speech in Brazil. As a powerful tool of social and political criticism, the freedom to do humor should not be so frequently relativized. Cases like the one of the blogger condemned to pay an indemnity of R$10.000,00 for having published a photomontage of the then mayor of Osasco, Emídio Pereira Souza, on the body of a pig to complain about the “garbage mafia” transmit uncertainty and insecurity to other citizens that intend to manifest themselves too. In this sense, the fear of a conviction generates chilling effects on free speech.

In the same time that decisions like this are made, draft bills advance in national Congress with the aim to facilitate the removal of content of the Internet and broaden the possibilities of holding people liable for the so called “crimes against the honor” (reputational harms), like Bill n. 5203/2016 (that establishes the obligation of Internet providers to monitor — and remove — contents that were the objects of legal removal requests), Bill n. 1676/2015 (that makes recording someone’s voice and image without authorization a crime and establishes, in the Brazilian law, a kind of “right to be forgotten”), and Bill n. 215/2015 (that deals with crimes against the honor).

Especially on a year of municipal elections, in which local relations accentuate even more the correlation between power and constraint on freedom of expression, and in a context in which the Internet has become such a fertile stage for political discussions, decisions that do not put the freedom to do humor above frivolous reputational harm claims threaten not only the right to free speech, but democracy itself.

[1] CF. Robert Alexy, A Theory of Constitutional Rights, 2nd ed., Malheiros Editores, São Paulo, 2008, p. 94-99.

By Dennys Antonialli