InternetLab Reports: Internet, Voices and Votes #2: Human Rights on the agenda

In the same line as the one we’ve pointing to last week, the Internet has shown itself as an interesting alternative for candidates to campaign over the last elections: the interaction with the voter can happen in a more direct way in a Facebook page than on a television debate. Online pages are also an opportunity for candidates with less resourceful campaigns to get more exposure and publicity. This is usually true especially when the candidate engages with polemic subjects, as they can position themselves quickly, or even generate network effects, such as the viralization of contents. This can be in their favor or not, of course.

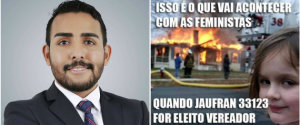

Last week, a case was quite exampleful of that: a candidate to the City Council of Natal (RN) by the PMN (National Mobilization Party), Jaufran Siqueira, published a meme, certainly in hopes of getting positive engaging, which generated an overwhelming response against himself. He produced a reinterpretation of a famous meme (the “disaster girl” — a kid smiling, satisfied, in front of a burning house), with the phrase “This is what will happen to feminists when Jaufran 33123 is elected”.

His attitude was reported almost two thousand times to the Regional Electoral Court (TRE/RN), from the interpretation that his attitude can be framed as the crime of the Article 243 of the Electoral Code (Law 4737/65): “Propaganda that will not be tolerated: III – of inciting attack against a person”. The happening was widely shared on the social networks, and the post itself — later deleted — was flooded with manifestations against it and also in support.

PMN itself, the party Jaufran was a part of, posted on its blog a rejection note to the candidate’s post, and opened a process for the expulsion and annulment of his candicacy at the Regional Electoral Court of Rio Grande do Norte. Apart from possibly having his candidacy revoked, the candidate may also be fined up to R$10,000.

Jaufran, who manifested himself against what he calls “gender ideology” and in favor of polemic campaigns, such as “School Without Party”, responded to the accusations in his Facebook page, in several posts. Here are some parts:

“Natal: a city in which jokes need to be explained

Last Friday, 26, I published in my social networks a postcard in the format of a meme, in which I, using humor, show my opposition to the feminist movement.

First of all, I want to be very clear that I am totally against the feminist movement, because this movement does not defend the values of women, but the transformation of them into mere objects of social action, whose finality is not the ascension of women in society, but only the destruction of a culture that was built over the last 2000 years in the western world.”

“(…)My theoretical-methodological opposition to feminism has as a mission to denounce the real objectives of this movement, such as, for example, the sexual perversion and the destruction of family. These goals are clear in books, for example, Shulamith Firestone in her book The Dialectics of Sex, on pages 59 and 240.

The Party of National Mobilization (PMN) of the city of Natal, in the night of August 30 2016 opened a process to expel me of the party, which would lead to the impugnation of my candidacy.

I repudiate this attempt to censor and demage me, in virtue of the empire of the politically correct and the lack of good sense. I will fight to the last legal circumstances to keep my candidacy alive and to lead the voice of the people of Natal who lack in representatives who speak their voice and who are not afraid of the politically correct and the leftist movements (…)”

The positions that the candidate have been externing on the Internet show themselves contrary to the agenda related to Human Rights, mainly in what refers to the rights of women. Although positions alligned with his are very likely shared by many other candidates over the Brazilian municipes, to identify them is not always so simple for the voterr — the number of candidates is too big and not all of them use the social networks in the same way or have a page of their own for the campaign.

This difficulty is at the starting point of an initiative released on September 6th, the project #MeRepresenta (#RepresentsMe).

Idealized by #VoteLGBT, Rede Feminina de Juristas (Feminist Network of Jurists, #DeFEMde), AgoraÉQueSãoElas, #RedeNossasCidades, #LGBTBrasil and #CFEMEA, #MeRepresenta has as a goal to invite candidates to City Council positions to answer a questionnaire to identify their opinions surrounding 14 topics related to Human Rights; in their turn, the voters will be able to respond to the same questions and then match a candidate, that is, to find out with whom they have more affinity: “a political Tinder” — on the loose description of one of their founders, Evorah Cardoso.

The platform is open for candidates from all over the country, but the systematic/active search for candidates will happen in four cities: São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Recife and Porto Alegre. For that, the project is registering volunteers who will do the work in a prioritary virtual manner (via e-mail, Facebook and residually telephone) — a creative manifestation of Internet usage in the election process.

Beyond the adherence of candidates to the Human Rights agenda, the initiative aims to also evaluate the positionings of colligations and parties. According to the idealizers, the non-response to the questionnaire is also a data to be considered by at least two reasons: (i) the existence of ghost candidacies; (ii) the non participation of parties may indicate a resistance to the topics. Evorah Cardoso explains:

For this process, we created a manual of volunteer training, that will be applied in every city to guarantee the uniformity of the research. We limited the ways of contact and the number of times we will contact the candidates to talk about the platform. Why? For us, the non-response is also an interesting research data. Afterwards, we will process all these replies with an statistic to be able to tell, from them, which parties would have more candidates pro-human rights and which parties have the biggest index of non-response to the questionnaire.

Among this, we realized the existence of many filters/motives for the non-response. For example, we have to recognize that there are many ghost candidacies, especially of women candidates. This issue is already quite debated, as to how the 30% quota for women is accounted for to, actually, boost the 70% “quota” of men, who would be the actual candidates of the party. Therefore, as we searched of alternative means of contact in this research, we were able to indirectly approach the universe of ghost candidates. We are yet to know how we will process this data, but anyhow, it is an important filter to consider the non-response.

Another point to be considered as a filter would be the objections of the own parties. For example, an alternative way we follow to speed up the process of finding the candidate was the team itself getting in contact with the parties, explaining what the research was and asking for them to send us the lists of contacts. Some parties replied, but never with the complete list of candidates. There were parties who refused to send it, saying “we are not authorized to send this data” — this can also mean by itself a rejection to the issues the research addresses.

The case of the candidate for the City Council of Natal and the initiative #MeRepresenta show that the themes related to Human Rights have strength and visibility in the election process and raise important questions for the public debate — whether this discussion is brought up by candidate’s “initiative” (like in the case of the candidate, who manifested himself spontaneously about what he thought of feminism) or by provocation of third parties and self-organization of the civil society (as in the case of #MeRepresenta, that questions candidates about their positions).

On the interview below, Evorah Cardoso, one of the people behind #MeRepresenta, talks about the potential, but also the great range of difficulties that this kind of project involves, from the operational and methodological point of view. That is, how to really get the commitment of the candidates on human rights? Read:

InternetLab: Could you explain how #MeRepresenta will work? — the goal and the operation?

Evorah: It will be a platform that will be used for the registration of candidates via Facebook. They will answer 14 questions on human rights issues, and these same questions will be made to voters. Based on the crossing of the answers of the voters with the ones from candidates, the platform will show which candidates and voters “match” — a kind of political Tinder.

The Electoral Justice, through the “DivulgaCand”, released the e-mail addresses of all candidates in Brazil. Then, at first, we will send an e-mail with an automated invitation for all of these candidates to take part into the #MeRepresenta platform and answer the 14 questions — this is what we will do all over Brazil. The problem is that there is a distortion here and there, because who made this register in the Electoral Justice were the political parties, and we noticed that there are some generic e-mails, that are not exactly those of the candidates. In the cities in which we proposed to do the research, the volunteers will go after complementary contact sources, like: alternative e-mails to those released by the Electoral Justice, their personal or the campaign’s Facebook profile, telephone, etc.

For this process, we created a manual of volunteer training, that will be applied in every city to guarantee the uniformity of the research. We limited the ways of contact and the number of times we will contact the candidates to talk about the platform. Why? For us, the non-response is also an interesting research data. Afterwards, we will process all these replies with an statistic to be able to tell, from them, which parties would have more candidates pro-human rights and which parties have the biggest index of non-response to the questionnaire.

Among this, we realized the existence of many filters/motives for the non-response. For example, we have to recognize that there are many ghost candidacies, especially of women candidates. This issue is already quite debated, as to how the 30% quota for women is accounted for to, actually, boost the 70% “quota” of men, who would be the actual candidates of the party. Therefore, as we searched of alternative means of contact in this research, we were able to indirectly approach the universe of ghost candidates. We are yet to know how we will process this data, but anyhow, it is an important filter to consider the non-response.

Another point to be considered as a filter would be the objections of the own parties. For example, an alternative way we follow to speed up the process of finding the candidate was the team itself getting in contact with the parties, explaining what the research was and asking for them to send us the lists of contacts. Some parties replied, but never with the complete list of candidates. There were parties who refused to send it, saying “we are not authorized to send this data” — this can also mean by itself a rejection to the issues the research addresses.

Lastly, these 14 questions on the human rights agenda were selected from historical demands brought by the social movements, but we also tried to bring the maximum concretude possible to each of this issues and questions. Why? Because we are only giving “yes” or “no” alternatives for the candidate to respond, since we want to know if they agree or not, without allowing much interpretation. They are very concrete questions, that can become more difficult to answer. The questions are truly a watershed to know in which side people are.

InternetLab: This kind of project has been arising on the Internet and, from the outside, it seems to occur spontaneously. We know that it usually isn’t like that. In this case, how did the organizations gather around this initiative, and from which diagnosis specifically?

Evorah: Actually, there was a meeting of several entities, collectives, NGOs that were already thinking about how to cover the elections. The #VoteLGBT was already working with something similar since 2014, digging up candidates who had pro-LGBT agendas — that year it managed to bring up 270 candidates with pro-LGBT profiles.

The Rede Feminina de Juristas [#DeFemDe] was also thinking about making some sort of monitoring of the public policies proposed by the candidates. The #AgoraÉQueSão Elas in Rio de Janeiro was talking to the Rede Nossas Cidades (Our Cities Network), that had already made in the last elections — I believe in Rio de Janeiro — a platform called “Truth or Dare”. The idea of this platform was alto to make this “match“ between candidates and voters based on issues they stood by or not.

At the end of the day, if the #VoteLGBT were to work alone, we would only have LGBT agendas. If the Rede Feminina de Juristas were to work alone, it would only have feminist agendas. So, we were adding everyone up and are building this platform.

We also have the partnership with CFEMEA (Feminist Center for Studies and Assessment) and with LGBT Brazil. The LGBT Brazil is a big group that emerged still in the times of Orkut and then migrated to Facebook. It was the biggest LGBT community in Orkut and as volunteers they have already made an evaluation of the parties in previous elections from a ranking, pointing the parties with which we have to be very careful, which are trustworthy, etc. The CFEMEA is a NGO from Brasília that works with lobby and gender inside the National Congress — it is a super traditional organization.

Ultimately, along with LGBT Brazil and with CFEMEA, we are building an evaluation methodology of the parties for this election, and the idea that an initiative like this was needed came from the adding of efforts of several organizations that were already working in this isolatedly, but that realized that it could be much more potentialized in group.

InternetLab: What was the selection criteria for the participating cities, that is, those in which there will be an effort for really search the candidates, in an active way?

Evorah: The selection of the participating cities came from the presence from the articulations that we were able to sew in this several cities. Vote LGBT and Rede Feminina de Juristas were working here in São Paulo, #AgoraÉQueSãoElas there in Rio. When the Rede Nossas Cidades comes in, we have a bigger coverage and we are able to also include Recife, Porto Alegre, because there is the presence of the Rede there — so, there is “Meu Rio”, “Meu Recife”, “Minha Porto Alegre”, “Minha Sampa”. The selection criteria of the participating cities were also resulting of this. They are also important cities: capitals, politically representative.

InternetLab: You are having difficulties in relation to the registering of volunteers?

Evorah: We did a successful campaign in the social networks to get volunteers in all of the cities. There are hundreds of volunteers, the engaging was overwhelming and we are almost completing all the volunteering positions in these cities. People really want to contribute to guideline this elections with human rights. The aim is to have a number enough to enable an active search of candidates in the locations we proposed to do the research.

InternetLab: The idea, then, is to map the affinity of the candidates with the agendas. But will you also follow the mandate, and check if it matches their given answers? That is, is there a plan of extending the project beyond the election period?

Evorah: We haven’t got a closed work plan for this. It would be super interesting, but it isn’t yet on the radar. Anyway, for example, the evaluation methodology of the colligations and parties can be used in future elections — even if we can’t develop everything in full swing, it will serve for the next elections.

InternetLab: We know that not necessarily all candidates who call themselves “representatives” of a certain society sector (for example, women) advocate agendas for the advance of that group (for example, feminism). That is, not necessarily a candidate that belongs to a group who has their rights violated will be a representative of the discussions about those rights. Do you have any reflection about this, in the scope of the project?

Evorah: Look, I can talk in part as how #VoteLGBT, who works with two kinds of representativity. The first kind is based on the fact the the presence of LGBT, women and black people in congress matters — this degree of representativity is super important. Visibility and participation for itself are already really important. Now [in second place], the platform we are building is precisely to allow the identification among those candidates that, independently from being LGBT, or women, or black, that identify themselves and that stand for these human rights topics.

It is in those two levels that Vote LGBT works the issue of representativity, it is important to have LGBT people and it is important to have people that take the LGBT agenda forward, independently from being LGBT. I think it is in this second sense that the platform #MeRepresenta works, because it is making an extensive research with all of the candidates.

InternetLab: Could you comment how you see the relation (or interaction) of #MeRepresenta with other projects about representativity and the elections, such as “Vote numa Feminista” (Vote for a Feminist), “Enegreça seu voto” (Make your vote black) and “Candidaturas Trans do Brasil” (Trans Candidacies of Brazil)?

Evorah: We know all of those pages and think their work is super important. Specifically, we are following Vote Trans, because there is a terrible distortion of the Electoral Justice that still does not recognize trans people’s gender identity in the candidacy registration. We have trans candidates whose full name on the candidate promotion page of the Electoral Justice is not the one they identify themselves with. This is inadmissible. This mapping of trans candidates is also good to help us to not commit any mistake on the contact of the volunteers with the candidates, for example. Another way we have to minimize this type of mistake is to compare the full name with the urn name. Anyhow, it is a super important work to give visibility to trans candidacies. Inside the LGBT universe, trans people are those who suffer most with rights violation, so, it is important to give them the appropriate emphasis. Trans people have specific demands for the public authorities that suffer way more rejection in relation to other kinds of demands, and that has to be taken into consideration.

Team responsible for the content: Mariana Giorgetti Valente (mariana@internetlab.org.br), Natália Neris (natalia.neris@internetlab.org.br), Juliana Pacetta Ruiz (juliana.ruiz@internetlab.org.br) and Clarice Tambelli (clarice.tambelli@internetlab.org.br).

Translation: Ana Luiza Araujo